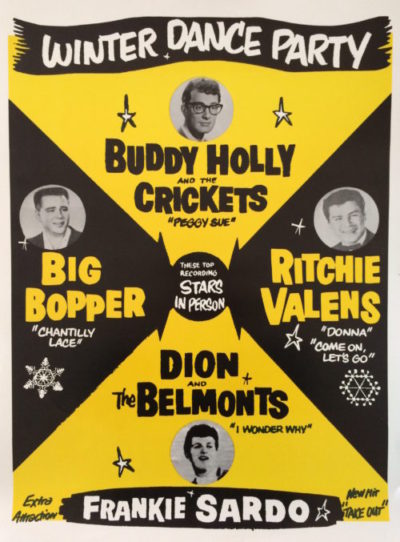

Everyone knows what happened the day the music died. Richie Valens, JP ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson, and most famously of all Buddy Holly all died in an aeroplane crash on route to their next venue.

The question is, how did Buddy Holly get into that situation? The next big thing in the then-new craze of Rock and Roll, countless hits, all written by him, one of the first to do so in the genre, one would think he would start to have some power in the music industry. It turns out that this wasn’t the case. This week, The Beat Marches On to 3rd February 1959, the day of that fateful plane crash.

Buddy Holly was the next step in rock and roll. Where the early stars like Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and Jerry Lee Lewis had people write their songs for them, Holly wrote and performed his own songs.

After a failed couple of singles when signed with Decca in 1956, Holly decided to record his songs at a studio owned by his manager, Norman Petty, who also looked after the finances. From the first couple of years, the deal worked out fine. Buddy and his backing band, the Crickets, Jerry Allison and Joe B. Mauldin, had nine top 30 hits in the UK.

By August 1958, though, things had changed. Holly had fallen in love, got married, and was expecting his first child. He had never been the biggest fan of touring either; now that he was settling down with his new wife, he wanted a change in his career.

Instead of being a musical performer, Buddy now just wanted to be a songwriter and producer. He couldn’t do that in his home base of Lubbock, Texas; his wife, Maria Elanor Santiago, was based in New York. At the time, the Big Apple was the epicentre for music in the US. The Crickets wanted to stay in Texas, as did Petty. The split was amicable for now.

The split was less amicable when, as with most things, money got involved. Holly, who had no income at this time and a pregnant wife to support, asked Petty for some of the royalties he had earned from his many hit singles. His manager went silent.

Buddy needed money fast. He didn’t want to go on tour, but he knew that was the quickest way to earn money. He agreed to headline a tour around the Midwest states called the Winter Dance tour.

The tour was intense. 24 dates in 25 days. The organisation of the tour was a disaster. The geographical planning was diabolical. Starting in Milwaukee, the tour criss-crossed throughout the states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. The first ten dates covered 2,467 miles.

The party was a package tour featuring Holly and a newly formed Crickets with future country star Waylon Jennings on bass, Tommy Allsup on guitar, and Carl Bunch on drums. Dion and the Belmonts, a Do-Wop group who had minor ballad hits No One Knows and Don’t Pity Me and were soon to have the major hit with a version of A Teenager in Love. Richie Valens, aged just 17, was the first Hispanic rock and roll star and had a big hit with La Bamba. J.P ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson, who was a DJ and a novelty singer, was known for the hit Chantilly Lace and also released The Purple People Eater meets The Witch Doctor. Eddie Cochran was offered to co-headline with Buddy but declined due to an offer to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show.

The travel was horrible for the tour. They travelled by bus from stop to stop, and this wasn’t a tour bus; it was a converted school bus. It was unreliable, and by the first 10 stops of the tour, they were on their eighth bus. The weather was terrible, one of the worst on record, with 13 inches of snow at the first stop in Milwaukee and an air temperature of -15F (-27C)

There was one breakdown in particular that led to the decision to start flying to venues. The bus predictably broke down, but they were stuck in the middle of nowhere. There was no power coming from the vehicle, and the weather had got even colder down to -21F (-31C). Just to keep everyone warm, a fire had to be started on the bus. The entourage did get rescued, but they would never be the same again.

The weather was so bad that The Crickets drummer Carl Bunch had to quit the tour due to getting frostbite on his feet. The band was playing the backing tracks for most of the acts on the tour. Instead of getting a replacement drummer, Carlo Mastrangelo of the Belmonts, Valens, and Holly himself filled in on drum duties.

There was another breakdown the day before the fateful flight. This time, they made it to the venue in Clear Lake, Iowa, and there was a rush to get organised as it was only two hours to showtime.

Due to the long delay with the broken-down bus, the touring party couldn’t make the next date. There was a long trip to the next venue. Holly had enough of the buses. He was going to charter a plane.

Buddy got in touch with a local plane service in the next town, Mason City, and booked a flight to Fargo, North Dakota. From there, he would travel to Moorhead, Minnesota, a five-minute drive. There was limited seating on the plane. Enough for Holly and two others, his choice was his fellow band members, Allsup and Jennings, who would change by the time they left for the airport.

When the rest of the tour got wind of the chartered plane, they tried everything to get a seat. The Big Bopper was suffering from the flu and needed medical attention. Jennings felt sympathy for him and offered to swap his seat. This led to a joke between Holly and his bassist, which, with hindsight, was ill-timed, with Buddy saying ‘I hope your ol’ bus freezes up’ and Jennings replying ‘Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes’ which he regretted saying for the rest of his life.

After that night’s show, Buddy entered the car that transported him to the airport not only without Jennings, but also Allsup. At the last minute, he flipped a coin with Valens to see who would get the final seat. The La Bamba singer had been pestering the guitarist throughout the whole evening to try and get a seat on the plane, and finally, he caved in. This was reportedly the first time Valens had won anything.

The trio got to the airport ready for the 12:55 flight, bringing everyone’s dirty laundry with them, as a chance to go to a Laundrette was impossible with the long travel in between shows. The weather reported that there was a snowstorm coming in, and it wasn’t going to affect the flight. The snow came in much quicker than expected.

By the time the plane took off, there were some light flurries of snow in the air. The pilot, Roger Peterson, aged just 21, wasn’t qualified to fly in conditions with low visibility yet. He had passed the theory but not the practical. The plane company, Dwyer Flying Service, wasn’t even licensed to fly in low-visibility conditions.

The owner of Dwyer Flying Service, Hubert Jerry Dwyer, manned the control tower, and the flight took off without a hitch. It wasn’t long until he feared the worst, though. Around four to five miles from takeoff, he saw the lights on the aircraft disappear. Peterson was supposed to radio in at 01:00, and when there was nothing but silence, Dwyer knew it was deafening.

The flight lasted just six miles. The plane had crashed in a corn field northwest of Clear Lake. The estimated speed of the impact was 170mph. There were no survivors. Dwyer couldn’t get out and check what was going on until morning. He traced the flight path in another plane and was the first one to see the wreckage.

The rest of the tour didn’t know until they got to Moorhead. There was some confusion about who was on the plane originally. Some news reports said it was Allsup and Jennings, others said Valens and the Big Bopper. They all agreed that Holly was one of the victims.

Maria Elana Holly had heard about her husband’s death through the TV reports. She was told not to turn on the TV, but she quipped back with ‘Well, of course, when someone tells you not to do something like that, you do it right away’ The trauma of finding out caused Maria to miscarry. She was so distraught that she wouldn’t attend her husband’s funeral.

Amazingly, the tour carried on. Even that night’s performance in Moorhead. The organisers brought in a then unknown local school child, Bobby Vee, a 15-year-old, who knew all of Holly’s songs. Vee got some of his school friends to form a band called the Shadows and played for the mourning audience. The rest of the tour remarked how eerily close he sounded to Buddy. Vee would go on to have multiple top ten hits on either side of the Atlantic. For the rest of the tour Jimmy Clanton, Fabian, and Frankie Avalon were replacements for the rest of the tour.

It felt like the plane crash was the end of 1950s rock and roll. Holly was the next big deal in the genre. With Elvis in the Army, by the end of 1959, Chuck Berry would be arrested, Little Richard turning his back on the devil’s music and leaning into gospel music, and Jerry Lee Lewis being, well, Jerry Lee Lewis. The big stars were leaving the limelight quickly. Even the DJs playing the records were getting caught up in scandals, and it looked like rock and roll was on its knees. Of course, it wasn’t the end, as at one of the stops on the tour, in Deluth a member of the next generation that would make the 1960s so prevalent was watching Holly and the new Crickets. Bob Dylan, after watching his idol, was inspired to start writing his own songs, and he did okay for himself.

The Beat Marches On is a music blog written by Jimmy Whitehead. Jimmy has been blogging for nine years, specialising in Sports (especially American Football). If you want to follow Jimmy on Twitter: @Jimmy_W1987

The Beat Marches On has a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/The-Beat-Goes-On-Blog-107727714415791 and an X page: @TheBeatGoesOnB1

Websites used for research were:

Inside Buddy Holly’s Death In A Plane Crash And ‘The Day The Music Died’

Remembering The Day The Music Died: Part One – The Prologue – American Blues Scene

The podcast A History of Rock in 500 Songs was an inspiration for this article.

For the information on the flight, the YouTube channels Pilot Debrief and Disaster Breakdown were used.

If you want to request a story for The Beat Marches On blog, you can contact jwhiteheadjournalism@gmail.com. We cannot guarantee that the story will be published, but it will be considered.